Mastering the Municipal Reuse Master Planning Process

This article has been adapted from “Addressing Water Supply Gaps with Reuse: Tailoring a Reuse Master Plan for Your Needs,” a recent webinar from CDM Smith featuring the expertise of Jillian Tedder, P.E. and Johnathon Sheets, PhD, PE.. Stream the full webinar here and earn a PDH for attending.

When it comes to reuse master planning, every entity has different needs and therefore projects will range in size and scope. To help find the right plan for you, we have broken down the process into a few steps.

1. Understanding growth:

The growth assessment is often part of broader planning efforts. It typically begins with population projections for a chosen planning horizon. Next, we examine the development pipeline, encompassing residential, commercial, and industrial sectors. For instance, we may consider the impact of tech companies entering a given area and evaluate their water demands and wastewater generation.

2. Evaluating Large Water Users:

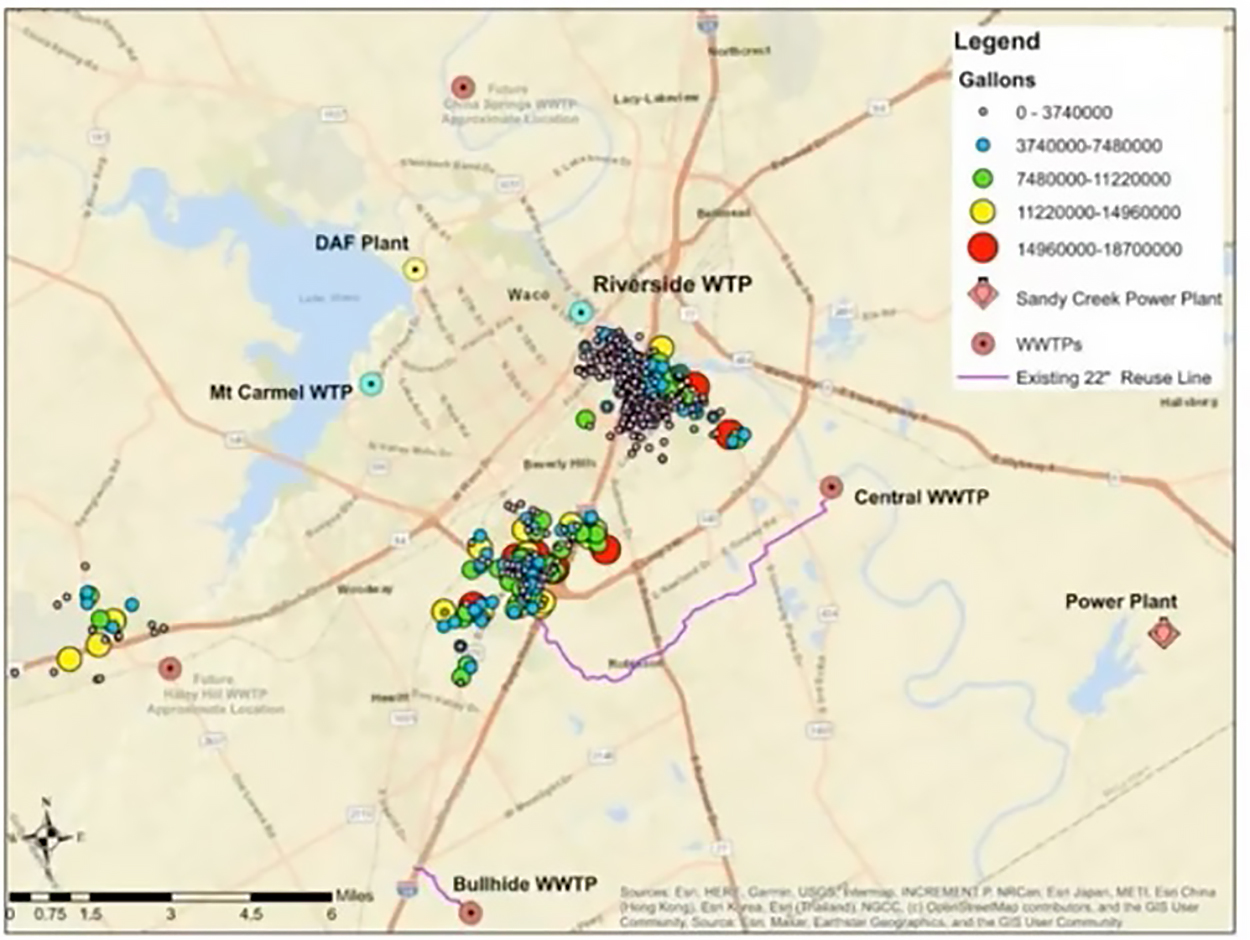

The methodology for evaluating large water users varies depending on the utility. In general, we utilize water billing data to determine the amount used for non-potable applications. Subsequently, we spatially map these users and group them into geographic areas that assist in identifying low-hanging fruit project opportunities. This analysis considers both current and future usage.

3. Evaluating Infrastructure, Capacity and Water Quality:

The next step is to evaluate infrastructure, capacity, and water quality. Oftentimes, condition times, condition assessments on existing infrastructure are performed. The conveyance coverage of the distribution pipe network is mapped such that potential future conveyance options for reuse can be explored.

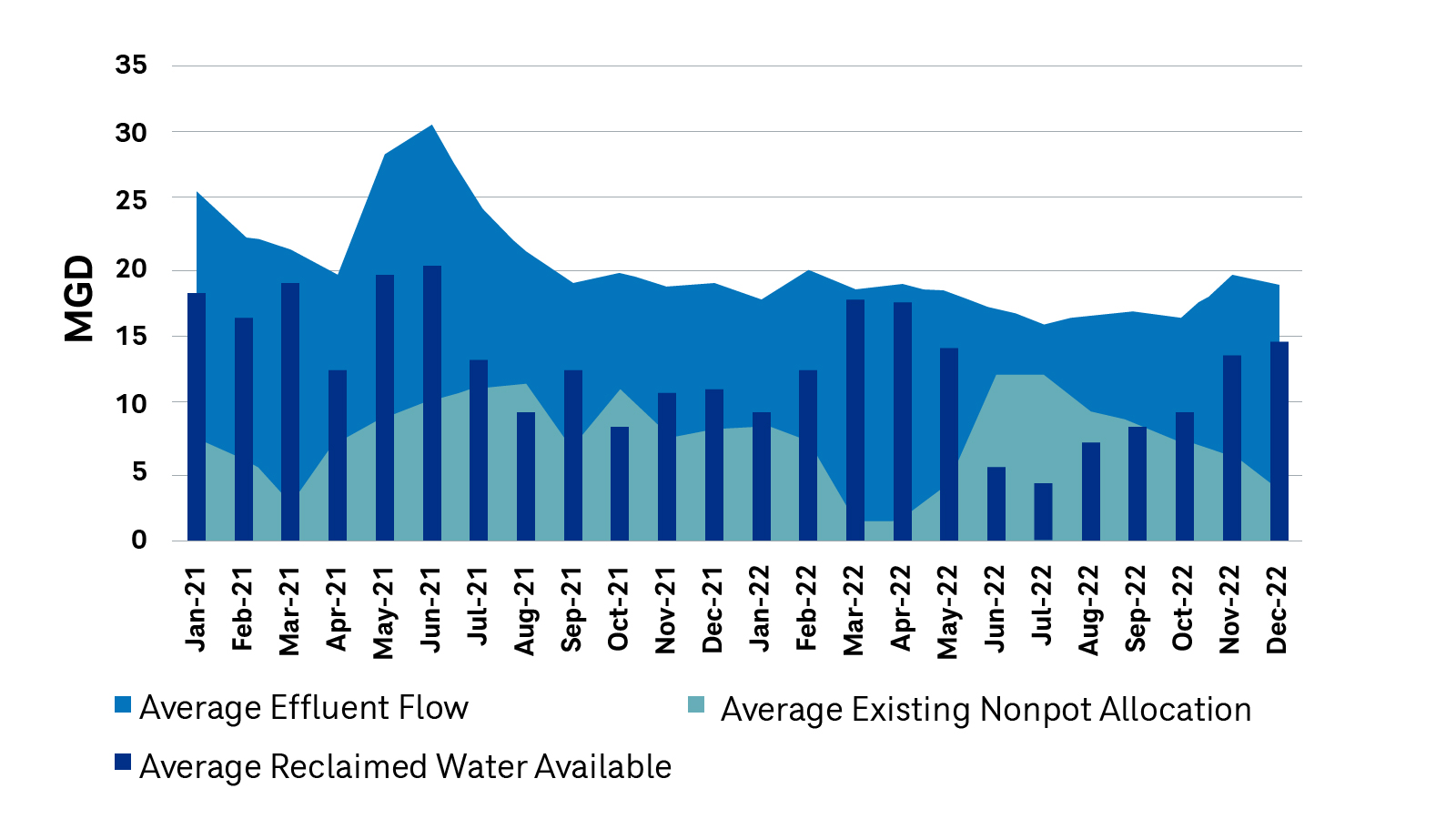

From a quantity standpoint, it’s crucial to consider reclaimed water availability. This availability depends on return flow requirements and any existing contracts related to non-potable reuse allocations.

Regarding water quality, we first delve into available historical data. Our analysis aims to determine whether the system can meet existing or projected regulatory standards for wastewater discharges and non-potable and/or potable reuse water regulations and guidance, which are state-specific. In many cases, there are supplemental sampling needs for critical source water evaluations which focus on both regulated and unregulated compounds.

4. Assess Existing Reclaimed Water Systems:

When evaluating existing reclaimed water systems, the capacity for expansion in terms of size and proximity to potential anchor users is explored in more detail.

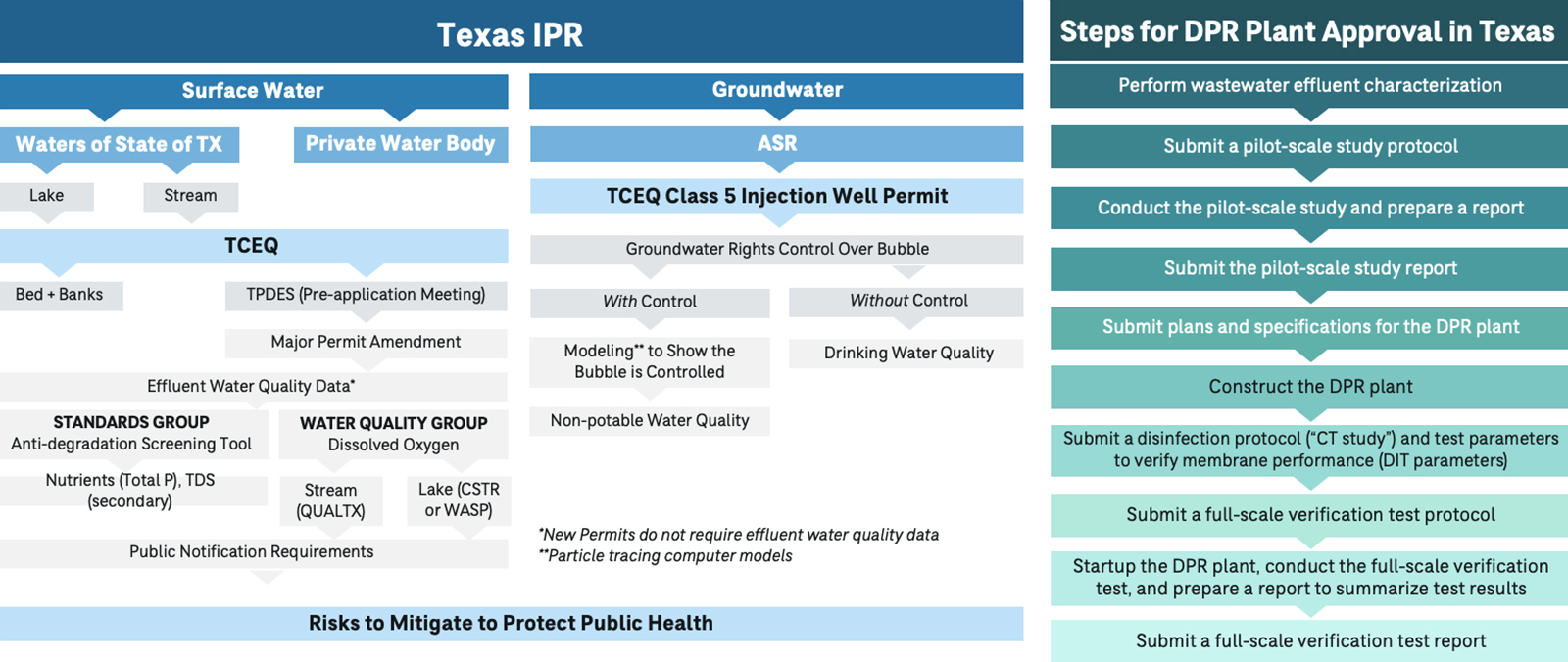

5. Define Regulatory Pathway:

Defining the regulatory pathway is an effort that is often underestimated, but the time commitment, cost, and effort required are not insignificant. The regulatory landscape varies significantly by state and application. Many states are adopting official direct potable reuse regulations, such as Colorado and California. it is crucial to consider the timeline required to develop a permit application and obtain approval for the project. This time frame should be factored into the overall implementation timelines for each of the project alternatives.

6. Form Projects and Develop Planning Level Costs:

Finally, we collaboratively develop project alternatives with our clients, which typically also involves visual representations of each alternative in terms of new infrastructure, conveyance, storage, wastewater treatment plant improvements, and water treatment plant enhancements such as advanced treatment processes. Next, we qualitatively assess the benefits and potential risks associated with each option.

Planning level costs development incorporates capital and operational and maintenance (O&M) costs. We cost capital improvements such as plant upgrades, advanced treatment, conveyance, storage, pump stations and site improvements. Additionally, we account for supplemental costs that should not be overlooked, such as source water characterization, piloting, permitting, and public outreach programs critical in the success of non-potable and potable reuse projects.

These project alternatives and planning-level costs are often integrated into another multi-criteria decision-making process such as an IWRP or One Water Plan. Decision-making processes typically outline metrics and performance criteria for each option, aiding utilities or corporations in prioritizing projects from the present into the future.

When it comes to reuse master planning, your unique needs should determine the size and scope of your project.